Parkhurst Prison

Parkhurst: The Boys’ Prison, 1838 - 1864

In 1828 the Select Committee of the Metropolitan Police heard from J. J. Capper, the Inspector of the Hulk Establishment, that the results of the juvenile hulk experiment (which involved many boys awaiting transportation being held either on the Euryalus or York hulk or being sent to Millbank Prison), were not encouraging. When asked what had been the conduct of the boys after release, he concluded: 'I am sorry to have to say it has been very indifferent for eight out of ten that have been liberated returned to there old careers.' After hearing the evidence the Select Committee recommended the abandonment of the use of hulks for boys and suggested that a separate juvenile prison should be provided. [1]

Despite this suggestion it was not until the 1835 Select Committee on gaols also recommended that a separate prison for juveniles should be established, and their recommendations gained parliamentary approval. Another committee was set up the following year to report on the proposed juvenile prison. Dartmoor was considered first, but the expense of conversion was considered to be too great. Porchester Castle, Waltham Abbey and Enfield Lock were also considered and dismissed for various reasons. On 18 July 1836 the Committee looked at Parkhurst, part of Albany Barracks on the Isle of Wight. The buildings under consideration stood in the centre of fifty acres of land owned by the Crown. The site was considered to be 'exceedingly healthy and remote enough from other buildings and having adequate water connection for the conveyance of convict boys to the prison and for their removal to the colonies when their period of confinement was expired.' [2]

The buildings had previously been used as a hospital for the barracks and as an asylum for invalid children from the military school at Chelsea. The proposition was approved and work started on converting the old hospital buildings into a juvenile prison to house 280 convicts.

The Parkhurst Act was passed in 1838, and for the first time in England a separate for young offenders was established. In the original Act both male and female offenders were mentioned, but when the prison opened only boys were admitted.

The following extracts are taken from the 1838 Parkhurst Act: -

3. It shall be lawful for one of Her Majesty's principal Secretaries of State to direct the removal to Parkhurst Prison of any young offender, male or female, under Sentence or Order of Transportation and those under sentence of Imprisonment, having been examined by an experienced Surgeon or Apothecary so appear free from any putrid or infectious distemper to be removed from the Gaol, Prison or place in which the offender shall be confined.

4. Every offender sent there shall continue there until they be transported or shall be entitled to their liberty or unless the Secretary of State shall direct the removal of such offenders to the gaol from which they have been brought.

5. The Secretary of State can at any time order any offender to be removed from Parkhurst Prison as incorrigible and in every such case the offender so removed shall be liable to be transported or confined under the original sentence to the full extent of the terms specified in the original sentence.[3]

It was on the 26th December that Robert Woollcombe, with a number of taskmasters, brought the first 102 boys to Parkhurst, and the prison was officially opened. Of these first boys 49 were from the York hulk and 53 from Millbank. When the first official report on the establishment, by the Prison Visitors and Robert Woollcombe, was submitted on 1st July 1839, 96 boys remained. In their report the Prison Visitors set out their objectives for the prison. It would aim at 'the general correction of the boy with a view to deter, not only himself, but juvenile offenders generally from the commission of crime.' They also hoped for the 'moral reformation of the culprit.' In his report Governor Woollcombe wrote: -

'Your Lordship is aware that no specific instructions for carrying on the several details of duty and discipline in the prison have been furnished me and that the rules and regulations approved by your Lordship for the general government of prisoners, ... [and] for establishing prisons for young offenders, refer only to the general points of government in the prison, and consequently, that it has been my duty in compliance with certain of these rules to submit to your Lordship, from time to time, such details of internal management as have presented themselves in my judgement best adapted for the required purpose.' [4]

In the same report the Reverend Thomas England, the prison chaplain, wrote: -

'Prison duties are performed by half-past-seven, every bed is made up, dormitories cleaned and ventilated and made ready for inspection, prisoners and cells are inspected. Prisoners then march to breakfast at 8 o'clock. From 8.30 to 9 there is a religious service and Bible reading. From 9 to 9.45 an exercise period and then work commences. There are thirty-three tailors, twenty shoemakers and two carpenters. 12 to 12.45 more exercise. 1 o'clock dinner. 1.30 back to their trades. 6 o'clock occupations cease and prisoners have supper. 6 to 7.30 school period and exercises. 7.30 another religious service. 8 o'clock the watchman comes on duty and prisoners are locked up for the night. One has fifteen years transportation; twelve have ten years and eighty have seven years.' [5]

Between 1838 and 1863 the prison was enlarged and extended, with much of the work being undertaken by the boys as part of their training in stonework, carpentry and ironworking. Provision was also made for workshops for tailors and shoemakers, and the land around the prison was used for employing the prisoners in agricultural labour.

Robert Woollcombe was to remain as governor of Parkhurst until his resignation in 1843 when his place was taken by George Hall, who was to remain as governor until Parkhurst closed as a boys' prison in 1864.

One of the first changes made by George Hall was to divide the prison into five wards: -

- A general ward

- A junior ward for boys under thirteen

- A probationary ward

- A refractory ward

- An infirmary ward

On arrival all boys were put into the Probationary Ward where they were confined in a separate cell for 4 months. During this time their capabilities and character were noted by the chaplain and an officer, and for most of the time the silent system was in force. Here they were taught to read, spell, write and calculate, and when not at school they spent their time picking oakum. After four months the boys were moved either to the Junior or General Ward, according to their age and on the recommendation of the chaplain.

In the Junior Ward the boys attended school for two and a half days a week, with the rest of the time being spent at work. A few were employed in the tailors' shop, others helped with pumping the prison water supply and the rest worked on the farm. All were taught to knit.

When they were 13, or before if their behaviour warranted it, they moved to the General Ward, where they were employed in a wider variety of employment, including shoemaking, brickmaking, blacksmithing, gardening, painting, cooking and laundry work, as well as agricultural labour, useful training for when they were released or sent to the colonies.

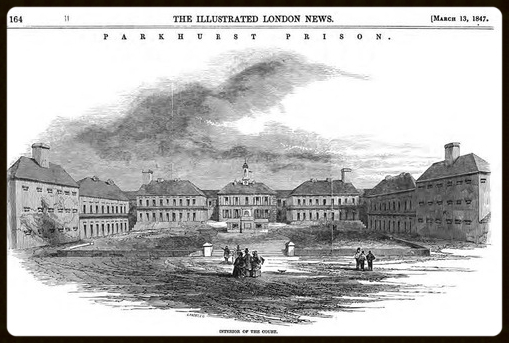

An article on Parkhurst Prison appeared in the Illustrated London News, 13 March 1847. I have quoted part of it here.

'The several buildings are of brick, with cement dressing; and the portions appropriated to the Prisoners are surrounded with walls fifteen feet high. The principal entrance is through a rusticated archway, of Isle of Wight stone; flanking which are two lodges, that on the left for the Porter; and on the right are the office of the Clerk of Works, the Surgery, and the receiving-room; in the latter are slipper baths, supply of hot water, and fumigating apparatus. Here each Prisoner, previous to admission, is examined by the Surgeon; is next washed, and clothed in Probationary Ward dress, entirely new. The Officers of the Prison wear military undress - blue frock-coats, cloth caps, and leather belt and strap holding keys. Each Prisoner wears a leather cap (made in the Shoemakers' shop) and bearing on its front the Boy's No.; and P.P. on the left thigh. The rest of the clothing is striped shirt, leather stock, waistcoat for winter wear, worsted stockings and boots, all of which are made in the Prison. On the right breast is worn a brass medal with No. The Penal Class is donated by yellow collars and cuffs, and letters of the same colour.' [6]

The food was basic, consisting of gruel for breakfast, until 1851 when this was replaced with bread and cocoa with molasses, for dinner a pint of very substantial soup on three days, and on the other four days three and a half ounces of boiled beef and broth with potatoes and bread, and for supper one pint of oatmeal gruel. The food was the same every day except Sunday when plum pudding was on the menu at dinner time.

In the 1853 Report of the select Committee Captain Donatus O'Brien tells us about the pudding.

'We have one special indulgence which may appear trivial - anybody who had anything to do with juveniles will know that you cannot get at them in any way so effectually as through their stomachs - and taking that into consideration we have added to the Sunday dinner a plum pudding. Boys who have committed any trivial offence are deprived of their pudding, they are marched out and paraded up and down the yard while those who have conducted themselves properly are eating their pudding. It may appear to many people absurd that it should be so but practically it has had a greater effect upon their conduct than almost all else.' [7]

Parkhurst Prison had its critics, particularly those who thought that conditions in the prison were better than they were in the workhouse. A particular opponent of the prison was Mrs Mary Carpenter, who was interested in the improvement of poorhouses, she resented the fact that criminal boys in Parkhurst were better housed, better fed and better trained than boys who had committed no crime, but because of poverty, found themselves in poor houses throughout the country.

The last boy to be sent from Parkhurst to Van Diemen's Land was John Robertjohn. He had been sentenced to 10 years transportation at Exeter in 1848 and spent four years at Parkhurst before being sent there in October 1852. The last boy to go to Western Australia was John Hearn, who had been tried at Clerkenwell in July 1849, was also sentenced to 10 years transportation. He left Parkhurst on 5th November 1852, and sailed from Plymouth on the Dudbrook on the 22nd November 1852.[8]

With the establishment of reformatories in the 1850's prison sentences for children gradually became shorter. In January 1856 boys from gaols other than Millbank were being sent to Parkhurst. The last boy to be admitted was 16 year old Frank Wilkins, from Manchester. He had been sentenced to one year for stealing lead. He arrived at Parkhurst on the 16th December 1863 and was returned to Manchester Gaol on the 13th April 1864 as the boys' section of Parkhurst Prison closed on that date, and the remaining 78 boys were transferred to Dartmoor Prison under the care of Captain George Hall, the late governor of Parkhurst.

Using the Parkhurst Prison Registers it is possible to find out who all these boys were, where and when they were tried and discharged.

Each entry in HO24/15 gives the following information: - When Received - From What Gaol - Name - Age - Crime - Where & When Convicted - Sentence - Read or Write - Trade - Gaoler's Report of Character - When Discharged & How Disposed Of.

If we take Arthur Biggs as an example we can find the following information from the Prison Register: -

WHEN RECEIVED: 26 December 1838

FROM WHAT GAOL: York Hulk

NAME: Arthur Biggs

AGE: 13

CRIME: Stealing a handkerchief, value 2s, the property of Mary Parker

WHERE & WHEN CONVICTED: Old Bailey 20 August 1838

SENTENCE: 7 years

READ OR WRITE: Both well

TRADE: Errand Boy

GAOLER'S REPORT OF CHARACTER: Good on board the Hulk

WHEN DISCHARGED & HOW DISPOSED OF: 31 May 1842 - Emigrant New Zealand

Using this information it is possible to find details of the trial of Arthur Biggs on The Proceedings of the Old Bailey website.

Proceedings of the Central Criminal Court, 20th August 1838 - COWAN Mayor Tenth Session, 1838 p761

2078. ARTHUR BIGGS was indicted for stealing, on the 9th of August 1 handkerchief, value 2s., the goods of Mary Parker, - 2nd COUNT, stating it to be the goods of Richard Sargent.

MARY PARKER. I am a widow, and keep a chandler's-shop at Batter- on the 9th of August, five or six young gentlemen came to my house - I had some silk handkerchiefs on my premises - I missed one of them when they were gone - this is the one - (looking at it) - Richard Sergent is a grocer in Wandsworth - I had it to wash for him.

Prisoner. A boy asked me to go over the bridge, and I did - he met our boys, and I went with them to the door.

Witness. I cannot say the prisoner was in the shop.

THOMAS DALEY (police-constable V127.) I heard of this in about half an hour afterwards - I got in a Chaise-cart, and met seven boys - the prisoner was about the centre of them - I looked, and saw the prisoner had got a bundle in his breast - I took him, and pulled out this handkerchief on his breast - he said he got it from the shop, but he did not take it.

Prisoner. When the boys saw the policeman coming, one of them said, "take care of this handkerchief" - I did so, and the officer took me.

GUILTY. Aged 12.- Transported for Seven Years.

**********

Although not yet complete I have been transcribing the Parkhurst Registers for some time now. I have also transcribed the census returns for Parkhurst Prison staff and families for 1841, 1851 & 1861, during which time the prison housed boys.

[1] Select Committee on Police of the Metropolis (1828) vi, pp 103-104

[2] Duckworth Jeanie. (2002) Fagin’s Children: Criminal Children in Victorian England. Hambledon and London pp 91 -92

[3] The Parkhurst Act, 1838

[4] Report of the Prison Inspectors (1839)

[5] Report of the Prison Inspectors (1839)

[6] Illustrated London News, 13th March 1847

[7] Select Committee on Criminal and Destitute Juveniles (1853) p822

[8] TNA – HO24/15 – Parkhurst Prison Register